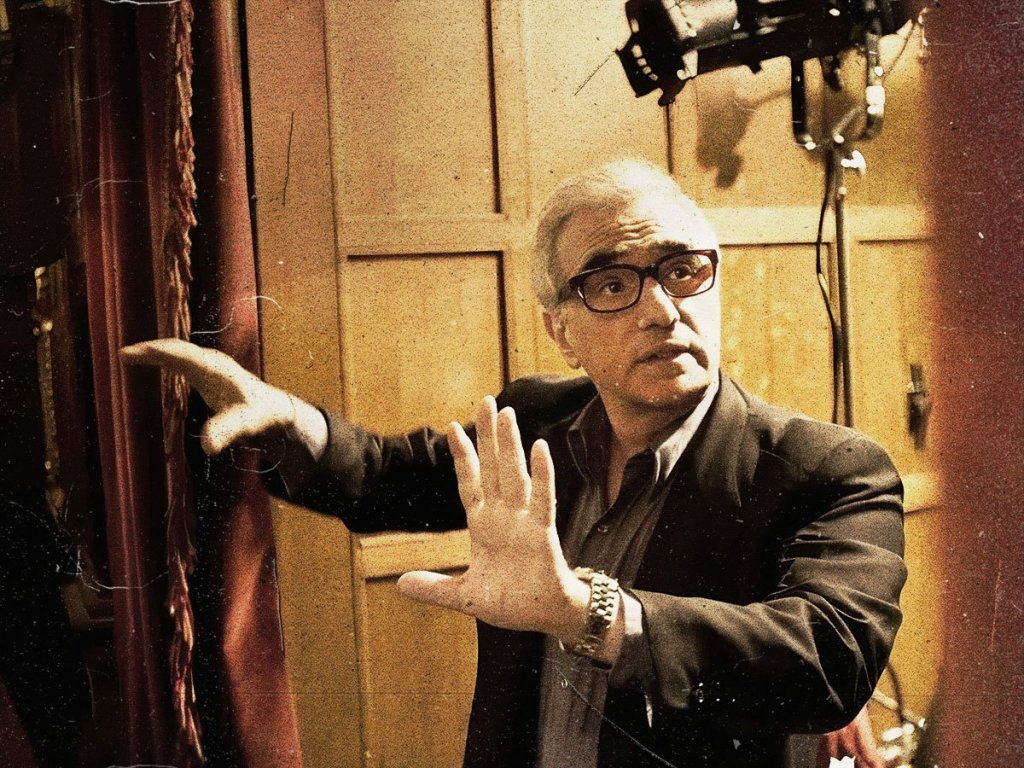

When I first became interested in filmmaking, Martin Scorsese was one of the first directors I was told to seek out. Whether his name was mentioned in my History of the Motion Picture class, or just conversations in passing, it was his movies that I would be looking for when browsing the aisles of the video store in search of that next great find.

What I’ve always loved about Scorsese’s work is that, despite being best known for his macho, gangster crime films, he has never been confined to a single genre. While those films rank among his greatest achievements, it’s the striking contrast between his projects that I find most admirable.

“Because of the movies I make, people get nervous, because they think of me as difficult and angry. I am difficult and angry, but they don’t expect a sense of humor. And the only thing that gets me through is a sense of humor.”

Martin Scorsese was born in the Flushing neighborhood of Queens in 1942 and grew up in New York City. Struggling with asthma, he was unable to participate in sports or outdoor activities, spending much of his childhood at the movies, where he developed a deep passion for cinema. His encyclopedic knowledge of film would later be showcased in the British documentary A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies. (The man has forgotten more about movies that most of us will likely ever know.) Initially planning to become a priest, Scorsese instead enrolled at NYU’s Washington Square College, where he earned his B.A. and M.A. between 1960 and 1968. During this time, he began directing short films and met long-time collaborators Harvey Keitel and editor Thelma Schoonmaker at the Tisch School of the Arts.

Scorsese spent the following years directing his first feature film, Who’s That Knocking at My Door?, and editing rock documentaries like Woodstock, before moving to Los Angeles. Within two weeks, he met future industry giants Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Francis Ford Coppola who introduced him to B-movie legend Roger Corman. Though hesitant to direct Corman’s Boxcar Bertha, he accepted the project, recognizing the creative freedom it allowed despite certain Corman-enforced guidelines (there must nudity every 15 minutes, and stay within budget). Armed with over 300 storyboards and influenced by the French New Wave, he infused the film with improvisation, private jokes, digressions, and auteurist references. This experience shaped his filmmaking style, marking the emergence of the real Martin Scorsese that we all know and love today.

DIRECTORS TRADEMARKS

The most obvious trademark in a Martin Scorsese film is a performance from either Robert De Niro or Leonardo DiCaprio. This one is so on the nose that there’s really no reason in pointing it out, other than right here:

- Robert De Niro: 10 Feature Films

- Leonardo DiCaprio: 6 Feature Films

Other trademarks worth mentioning but won’t be listed here are morally bankrupt protagonists, graphic violence, religious themes, and the liberal use of profanity in a majority of his pictures.

TRACKING SHOTS

Martin Scorsese’s tracking shots are iconic (maybe not as iconic as DePalma’s, but I digress), and they often create a sense of immersion that draws viewers into the world of his characters. These meticulous sequences not only showcase his technical prowess but also enhance the storytelling by allowing the audience to experience the unfolding drama in real-time. The most notable tracking shot that Scorsese is known for is in Goodfellas, but this technique is also featured in other films like Gangs of New York, and The Irishman, among others.

FREEZE FRAMES

Freeze frames serve as powerful visual punctuation, emphasizing pivotal moments and heightening emotional impact. This technique often invites viewers to reflect on a character’s internal struggle or the weight of a significant decision, enriching the storytelling experience. Whether it’s used to signify a specific moment that changes an individual life in Goodfellas, or slamming the breaks on an overstimulating moment in The King of Comedy, it often goes hand in hand with his next trademark, VoiceOver Narration.

VOICEOVER NARRATION

Sometimes the only way to (hopefully) sympathize with a character is to be able to hear the thoughts that are streaming inside that person’s head. Even if that person’s head is Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. They serve as a crucial storytelling device, providing insights into characters’ thoughts and motivations while adding an intimate layer to the narrative. This trademark has been used in numerous Scorsese films including Bringing Out The Dead, The Wolf of Wall Street, Casino, and Goodfellas, among others.

THE ROLLING STONES

Scorsese is famously known for his needle drops. Outside of Quentin Tarantino, Scorsese has had some of the most iconic movie soundtracks of the latter part of the 20th Century. But of all the artists featured in all of this films, I have often wondered where Scorsese’s career would be without The Rolling Stones, who are predominantly featured in at least four of his films: Mean Streets, Goodfellas, Casino, and The Departed.

CAMEOS

Scorsese also likes to have cameos in his own films. He even likes to feature his mother in bit parts. Finding the cameos of his mother is always a treat – an Easter Egg that’s always fun to hunt for in his earlier pictures. I also find it incredibly charming and sweet. Rumor has it that he started putting his mom in his movies as a good luck charm.

THE ESSENTIAL FIVE

TAXI DRIVER

“Loneliness has followed me my whole life. Everywhere. In bars, in cars, sidewalks, stores, everywhere. There’s no escape. I’m God’s lonely man…”

Taxi Driver (1976) follows the story of Travis Bickle, a mentally unstable Vietnam War veteran who becomes a vigilante in New York City, struggling with insomnia and his descent into isolation and violence as he seeks purpose in a morally decaying society.

I’ve always struggled to articulate why Taxi Driver resonates with me. I first watched it in my early 20s while immersing myself in 1970s cinema, and it left me speechless. Its unflinching exploration of alienation and moral decay, coupled with graphic violence and unsettling subject matter, made for a powerful yet deeply disturbing experience. While I admire the craft of filmmaking, Taxi Driver—like Raging Bull—is not a film I casually rewatch; I have to be in the right headspace to revisit its bleak, immersive world.

At the heart of the film is Travis Bickle’s naïve belief that he can cleanse the world of its corruption, despite the violent impulses simmering beneath his surface. His loneliness and insomnia warp his perception, creating a dangerous psychological spiral. Taxi Driver remains as unsettling, disturbing, and brilliant as ever, offering a haunting exploration of isolation and the fragility of the human mind.

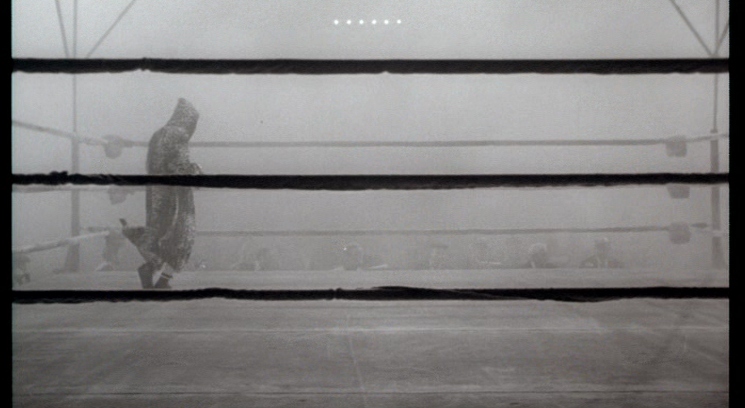

RAGING BULL

“I got these small hands. I got a little girl’s hands.”

Raging Bull (1980) is a biographical sports drama that chronicles the tumultuous life of boxer Jake LaMotta, whose ferocious career in the ring is marred by personal demons, jealousy, and destructive relationships.

Raging Bull was the hardest film for me to place on this list, largely because it’s the most difficult to revisit (even more so than Taxi Driver). It took multiple viewings in my late 20s to truly appreciate it, and even now, I struggle with its protagonist. While Jake LaMotta embodies the morally flawed characters Scorsese is known for, his sheer unlikeability makes the film especially challenging—yet also a testament to Robert De Niro’s brilliant performance. When I do rewatch it, I tend to focus more on the boxing matches, appreciating the many brilliant techniques with how – depending on the fight – the size of the ring changes, how much blood and violence shown, how each match is cut together, the slow motion, and the lighting of each of Jake’s opponents.

A masterclass in storytelling, Raging Bull delves deep into LaMotta’s psyche, exposing the destructive consequences of his rage and jealousy. Its brutal honesty and relentless intensity create a visceral, lasting impact, solidifying it as one of Scorsese’s most powerful films.

GOODFELLAS

“Paulie may have moved slow, but it was only because Paulie didn’t have to move for anybody.”

Goodfellas (1990) follows the rise and fall of Henry Hill, a young man who becomes deeply immersed in the mob underworld, navigating a life of crime, loyalty, and betrayal alongside his complex relationships with fellow gangsters.

I’m not sure if it was the first Scorsese film I intentionally sought out, but it was the first one that resonated with me instantly. Why was that? For two reasons: (1) I loved how the film romanticized the mafia and the criminal lifestyle, and (2) you couldn’t help but like Henry Hill. Is Henry Hill morally bankrupt? Possibly, but rather than complete ruin, he seems to be navigating a Chapter 13-style restructuring—holding onto just enough to stage a comeback.

Widely regarded as Scorsese’s best film (some will argue it’s Raging Bull, but they would be wrong), Goodfellas successfully immerses viewers into the complex world of organized crime with a perfect blend of drama and dark humor. The film’s kinetic, propulsive pacing makes its 2-hour-and-25-minute runtime feel more like an episode of The Sopranos, keeping audiences on the edge of their seats. Skillfully exploring themes of loyalty, power, and betrayal, Goodfellas is not just a gripping gangster tale, but a profound examination of the human condition.

THE AVIATOR

“He owns Pan-Am. He owns Congress. He owns the Civil Aeronautics Board. But he does not own the sky.”

The Aviator (2004) chronicles the tumultuous life of aviation pioneer Howard Hughes, exploring his rise to fame in the early days of Hollywood and aviation, while battling the crippling effects of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

I put off watching The Aviator for a while, though I’m not entirely sure why. Since 1995, I had made a point to see most of Scorsese’s films in theaters when possible, but after the disappointment of Gangs of New York, some of the excitement had faded. At that point, I wasn’t as eager anymore. The Aviator also felt like the first time Scorsese was actively chasing an Oscar, especially after being overlooked for Raging Bull and Goodfellas. (And yes, he was nominated for Gangs of New York—but let’s be honest, that wasn’t a snub. He simply didn’t deserve the win for that one.)

Thankfully The Aviator was so much than what I originally thought it was (which was chasing down that damn illusive Oscar). Scorsese’s encyclopedic knowledge of film history is on full exhibition here throughout the entire picture, where each era is shown in a different style of film stock and color palette, showcasing Robert Richardson’s breathtaking cinematography that captures the grandeur of early aviation and the lush environments of Hollywood — immersing viewers in Howard Hughes’s extraordinary world.

Hughes’s obsessive-compulsive tendencies, particularly his fear of germs, are deftly portrayed, highlighting his psychological struggles that accompany his passions for flight and filmmaking. Under Scorsese’s masterful direction, the film balances spectacular visuals with a deep psychological study, vividly depicting Hughes’s rise and fall as a pioneering genius plagued by his own demons. (The film will also make you never look at bottles of milk the same way ever again.)

THE DEPARTED

“One of us had to die. With me, it tends to be the other guy.”

In The Departed (2006), an undercover cop and a mole in the police force try to identify each other while infiltrating an Irish gang in Boston, leading to a high-stakes game of cat and mouse filled with suspense and betrayal.

Martin Scorsese returned to the familiar world of crime and gangsters with The Departed, though he was initially reluctant. Having been burned by studio executives before, he was hesitant to take on another genre film. After delivering two top-tier films for Miramax without securing the coveted Oscar, Scorsese finally won—ironically, not for a grand prestige piece, but for a hard-hitting, fast-paced and brutally violent B-movie remake of the Hong Kong thriller Infernal Affairs, where everyone is doomed from the start.

Not since Goodfellas has there been a better opening to a Scorsese film. It’s a master class of brilliant editing, exposition, shot-making, and music that pulls you in immediately and doesn’t let go for a good twenty minutes before you get a chance to catch your breath and gain your bearings again. The film is steeped in nihilism, packed with traitors and cutthroats. There’s hardly a genuinely likable character—most are morally bankrupt or devoid of morals entirely—yet you can’t look away. It’s a testament to Scorsese’s skill as a filmmaker that he can plunge into the depths of human depravity and still find his way to solid ground.

THE 6TH PICK (Honorable Mention)

THE WOLF OF WALL STREET

“The year I turned 26, as the head of my own brokerage firm, I made $49 million, which really pissed me off because it was three shy of a million a week.”

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) is a darkly comedic depiction of the rise and fall of Jordan Belfort, a stockbroker who engages in rampant corruption and fraud on Wall Street, fueled by a lifestyle of excess and hedonism.

Like every other Essential Five post I’ve put together so far, trying to fill the Honorable Mention slot has deemed very difficult. Depending on how expansive the filmmaker’s career is, the harder the decision becomes. This wasn’t any different. I chose The Wolf of Wall Street because it deserves to be here, but it is a very difficult film to recommend depending on the individual. It’s not for the faint of heart as it boldly and unabashedly puts on display a non-stop smorgasbord of sex, drugs, and flagrant consumption.

I’ve always said that The Wolf of Wall Street is basically Goodfellas set during the yuppie stock market boom of the 1980s, but that’s not completely true. Yes, the film centers around criminals who are performing criminal acts (except they don’t use guns, and there’s less violence). But it’s more than that. I guess a more accurate description is this: If The Wolf of Wall Street were a film cocktail, the recipe would be 2 parts Goodfellas, 1 part Wall Street, 1 part Boiler Room, 1 part Caligula, with a dash of Casino. Place in a mixing glass with ice. Shake vigorously and then pour into a cocaine-rimmed martini glass. Garnish with a quaalude and a $100 US dollar bill. Serve immediately.

Take every terrible and profane act that takes place in all of Scorsese’s films leading up to this moment in his career, combine them all, and then amplify it. That’s The Wolf of Wall Street. This film is debauchery in its purest form. Here he skillfully navigates us through the murky waters of human depravity (once again), leading its viewers through the muck, and while he isn’t able to locate solid ground this time, the picture sparks an internal debate: Does the film satirize its characters or is it a celebration its characters? The answer, of course, is both. And while Jordan Belfort isn’t any more likable than Jake LaMotta, here you feel more compelled to continue watching him because you want to see where it goes (even though you know it won’t be good). It is simultaneously both hilarious and disgusting, outlandish and repulsive, mesmerizing and loathsome, exhilarating and–by the end of its three hour run time–exhausting.

TRADEMARK | Tracking Shot

His most famous use of this technique, a long tracking shot following Henry Hill and his date Karen going into The Copacabana (the hottest spot north of Havana) through the back of the club. Film Geeks such as myself get super excited when we discover these types of scenes. The time and dedication it takes to setup and light a 3 minute shot while the camera and the cast are in constant motion is incredible.

This short clip from The Wolf of Wall Street captures a short but beautiful steadicam tracking shot.

TRADEMARK | Freeze Frames

There are a healthy amount of freeze frames throughout Goodfellas, but this one is my absolute favorite.

Below is one of the only freeze frames in The King of Comedy, where the audience is undoubtedly overstimulated by a group of raving fans that have surrounded Jerry’s Lewis’s character while another fan has jumped into his car. By freezing the frame, it slams the breaks on everything going on and lets us catch our breath before continuing.

TRADEMARK | The Rolling Stones

Most of Scorsese’s trademarks are often mashed together. Here’s a perfect example of combining Voiceover Narration while The Rolling Stones play during two different movies. The first is where we hear “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” from Casino, when Nicky starts to do his own thing out in Las Vegas. The second clip we hear “Gimme Shelter“playing underneath Frank Costello’s film opening narration from The Departed.

TRADEMARK | Voiceover Narration

You begin to notice the cracks in Travis Bickle’s psyche during this scene from Taxi Driver.

TRADEMARK | Cameo

Here are a few clips featuring his Martin Scorsese’s mother, Catherine. The first clip is from Casino. The second is from Goodfellas. Of course she was in more of his pictures, but these were the most prominent.

It was difficult to find other cameos of Scorsese on YouTube other than the most obvious one (which is the sick passenger from Taxi Driver). Thankfully, the video below has a collection of most of his cameos all the way up to The Wolf of Wall Street, whether he was on screen or it was just his voice (which happened more often than I first realized).

Lastly, while this isn’t a cameo in his own film, the fact that Martin Scorsese was willing to do an advertisement for American Express and make fun of himself at the same time, it’s always worth sharing.

KEY SCENES

Typically this is where I would go into the importance of each key scene I’ve procured here for you to watch, but instead I’ll just let the scenes speak for themselves. Thematically, you’ll probably experience a level of intensity and suspense throughout most of these scenes. That’s what Scorsese is so good at. Or making you feel uncomfortable. And quite often, you would feel both a the same time.

Further Viewing – A Cultivated Selection

I started getting a little lost in the weeds here—trying to figure out which movies to include and which to skip. I mean, I can’t just throw everything else into some giant ranked list; that’d be way too much. Plus, people already told me my Clint Eastwood post was so long it scared them off. That’s definitely not what I’m going for. So from now on, you’re only getting up to three more picks per director. Maybe even less, depending on the director.

UNDERRATED GEMS

Bringing Out the Dead (1999) is a hallucinatory descent into the chaos of nocturnal New York City, following a burnt-out paramedic (Nicolas Cage) haunted by the ghosts of those he failed to save. With stark, neon-drenched cinematography, Scorsese’s kinetic direction amplifies the film’s feverish intensity, while Cage delivers a mesmerizing performance of a man teetering on the edge of sanity.

PERFECTLY PAIRED WITH POPCORN

Cape Fear (1991) showcases Scorsese’s more sadistic and vicious nature, leaning hard into psychological horror with a sharp, stylized edge. Robert De Niro goes full throttle in one of his most unhinged and unsettling performances, turning Max Cady into a terrifying force of nature. It’s a fierce, pulpy thriller that fuses old-school noir with a bold ’90s intensity. It’ll also burn images into your brain that you’ll never be able to shake.

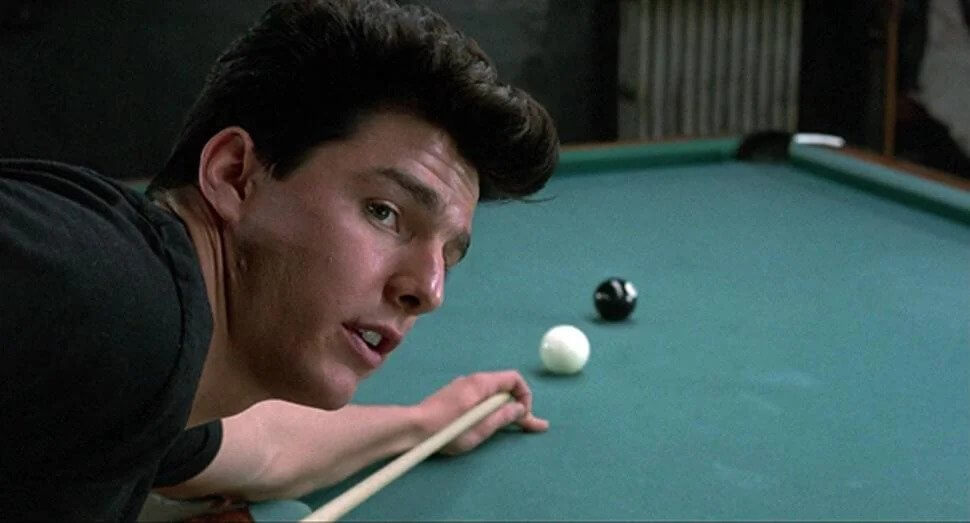

GUILTY PLEASURE

I don’t know if The Color of Money (1986) quite qualifies as a guilty pleasure—it’s solidly middle-tier Scorsese, but still a fun watch. You’ve got a smooth, seasoned Paul Newman going head-to-head with a young, cocky Tom Cruise, who’s clearly having a blast chewing the scenery early in his career.

Until Next Time, Dear Readers.

Leave a comment