His body of work was rarely the topic of discussion in the handful of filmmaking and video production classes I attended while at college. His name nor his genre defining work was mentioned by any of my instructors. However, once class had ended, that’s when I probably first heard the name, John Carpenter. That conversation with a random classmate probably went something like this:

Random Classmate: Have you seen Halloween?

Me: Halloween?

RC: Yeah, Halloween. You know, Michael Myers?

Me: Michael Myers? The guy from SNL?

RC: No, not Mike Myers. Michael Myers. You know, the Babysitter Killer? The Night He Came Back? Guy in a mask, jump suit, and a knife?

Me: I’m not a big fan of horror films.

RC: Dude, you need to rent Halloween. John Carpenter. The film basically invented the Slasher sub-genre on a shoestring budget and became one of the most financially successful independent films ever made. Dean Cundey’s camera work in that film is insane.

Me: Really?

RC: Trust me. You won’t be disappointed.

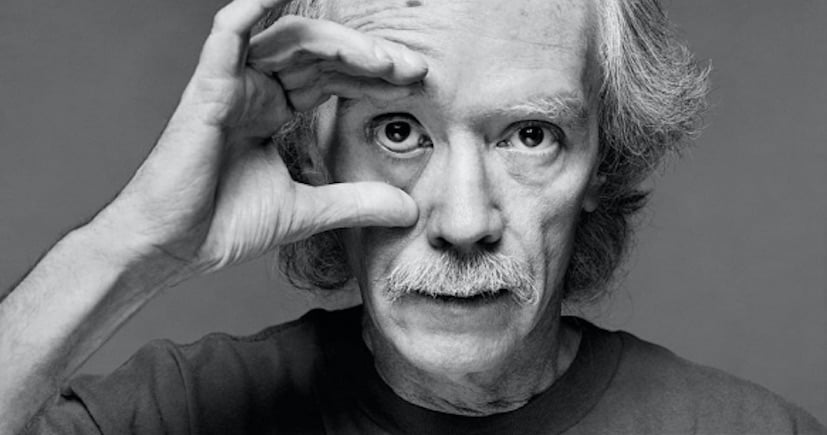

Widely regarded as a master of horror, John Carpenter’s work was often dismissed as lowbrow entertainment—appealing only to audiences seeking gore, cheap jump scares, and gratuitous nudity rather than meaningful cinema. But that reputation couldn’t be further from the truth. Carpenter was a visionary and a maverick within the Hollywood system, frequently choosing to work outside of the studio structure by independently financing his films. Though rarely embraced by critics or hailed alongside the darlings of the New Hollywood era, Carpenter carved his own path, pushing the boundaries of horror and science fiction while leaving behind a carefully crafted legacy of cult classics.

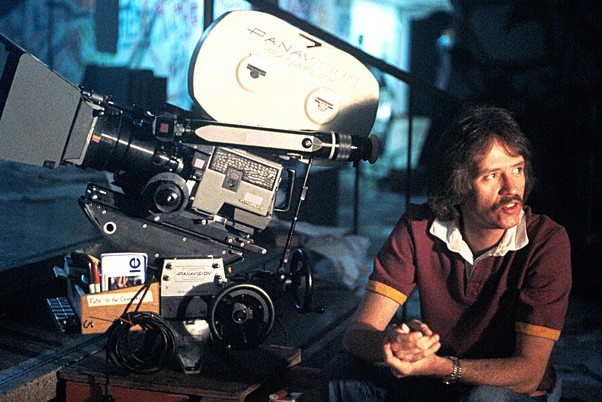

While he was born in New York in 1948, John Carpenter grew up in Bowling Green, Kentucky when his father, who was a music professor, took a job at Western Kentucky University. He discovered a passion for filmmaking at a young age, making several short horror films with an 8mm camera. After graduating high school, he studied English and History at WKU, but his desire was to study filmmaking, so he transferred to the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts, where he honed his skills in storytelling and direction. He eventually dropped out during his final semester to pursue expanding a 45-minute student project into his first feature film, Dark Star, which took three years to complete and showcased his innovative approach to science fiction. His success wouldn’t come until his third picture, a little independent horror that I may have already mentioned.

DIRECTOR’S TRADEMARKS

John Carpenter has at least four very distinct trademarks. You could probably argue that there are more, like his consistent history early in his career with Director of Photography Dean Cundey, or the five pictures he made Kurt Russell, but the four below are the only ones I’m listing.

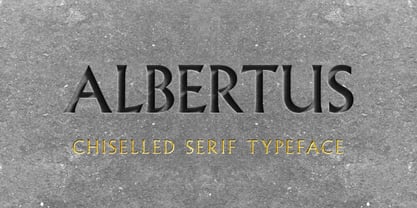

ALBERTUS TYPEFACE

I know I’m reaching a bit with this one, but if you’re a John Carpenter nerd (like me), then you know exactly what font I’m talking about. If you know who John Carpenter is, but you don’t know what I’m talking about in the slightest, then take a look below:

In almost every film he’s released since Halloween, he’s used the Albertus typeface font, especially in his opening credits. It may seem odd, but filmmakers often change styles throughout their career, and they aren’t always intimately involved with title cards. Yet, from 1978 to at least through most of the 1990s, the font that he’s used has remained the same.

MINIMALISTIC SCORES

They may be simple, repetitive, or even occasionally verging on the melodramatic—but one thing John Carpenter’s film scores are not is ineffective. Having composed the music for nearly all of his own films, Carpenter has crafted a distinctive sonic signature. His scores are remarkably effective due to their minimalist structure, atmospheric depth, and seamless integration with his storytelling, enhancing the tension and tone of his films in a way few other directors achieve.

BLEAK STORIES

John Carpenter’s films are rarely uplifting, and that’s no accident. He gravitates toward bleak narratives that mirror his worldview, artistic influences, and a clear intent to subvert audience expectations. In interviews, Carpenter has noted that happy endings often feel dishonest or contrived, favoring stories that confront darker, more unsettling truths. This perspective is exemplified in what he has dubbed his “Apocalypse Trilogy”—a thematic collection of films including The Thing (1982), Prince of Darkness (1987), and In the Mouth of Madness (1994)—each exploring the collapse of reality, society, or sanity (sometimes all three) in deeply existential terms.

RELUCTANT HEROES

From early on in his career, John Carpenter has had a clear fondness for the reluctant hero. His main characters are often everyday people who get pulled into chaos—whether it’s a convict helping defend a police precinct under siege, a babysitter fighting to survive a killer on the loose in her neighborhood, or a cocky truck driver who finds himself battling an ancient sorcerer beneath Chinatown. This kind of character shows up again and again in Carpenter’s films, and it’s pretty clear he loves putting unlikely heroes in way over their heads.

THE ESSENTIAL FIVE

HALLOWEEN

“It’s Halloween. Everyone’s entitled to one good scare.”

In Halloween (1978), a deranged killer named Michael Myers escapes from a mental institution and returns to his hometown to stalk and terrorize a group of teenagers on Halloween night, particularly targeting babysitter Laurie Strode.

By today’s standards, some might find Halloween tame—or even boring, as my wife bluntly puts it—but in 1978, it was anything but. Halloween is a near-perfect slasher film—tightly paced, beautifully shot, and clocking in at a lean 91 minutes. While it wasn’t the first slasher (with Psycho, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and Black Christmas laying much of the groundwork), Halloween refined the formula and helped launch the genre into mainstream popularity. Its simplicity is its strength: a straightforward plot elevated by smart cinematography, sharp editing, and an unforgettable, minimalist score.

When I first watched Halloween, it didn’t scare me the way I expected—maybe I saw it too late. But what it lacked in scares, it more than made up for in craftsmanship. Nothing about it feels cheap, despite the low budget, because every creative decision feels intentional. Carpenter, working with a talented team including cinematographer Dean Cundey, delivered a masterclass in resourceful filmmaking. It’s a testament to how vision, teamwork, and creative restraint can produce a film that still stands as one of the greatest in the genre half a century later.

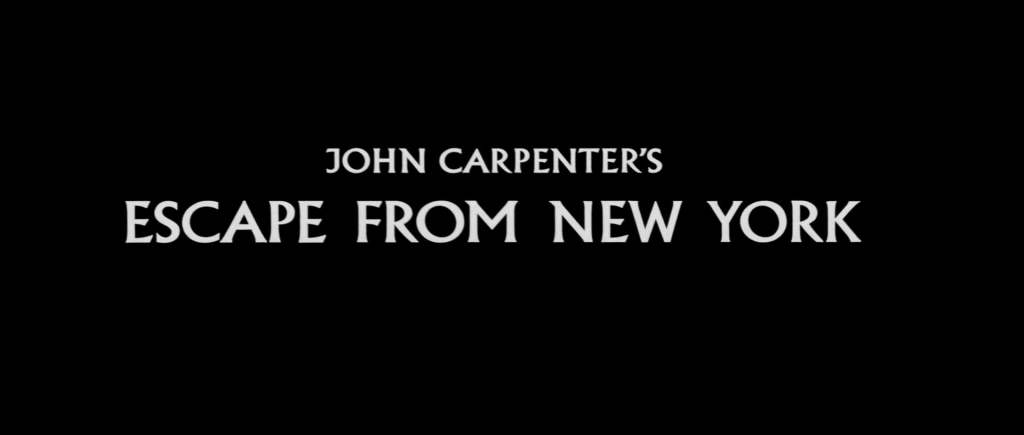

ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK

“Attention. You are now entering the Debarkation Area. No talking. No smoking. Follow the orange line to the Processing Area. The next scheduled departure to the prison is in two hours. You now have the option to terminate and be cremated on the premises. If you elect this option, notify the Duty Sergeant in your Processing Area.”

In Escape from New York (1981), a former soldier Snake Plissken is tasked with rescuing the President of the United States from the lawless streets of Manhattan, which is now a converted maximum-security prison.

John Carpenter has never been shy about weaving his views on politics and society into his films—sometimes subtly, as in Escape from New York, and other times with blunt force, as in They Live seven years later. In many ways, Snake Plissken serves as Carpenter’s on-screen alter ego: a hardened outsider operating on the fringes, much like Carpenter himself within the Hollywood system.

Escape from New York is a masterfully executed high-concept B-movie, elevated by inventive filmmaking. Working with a modest budget, Carpenter, cinematographer Dean Cundey, and production designer Joe Alves used creativity and resourcefulness to give the film an impressive sense of scale (it also helped that they filmed most of the picture in certain burned out neighborhoods in St. Louis). Their craftsmanship is a big part of why the film still resonates more than four decades later. It’s easily one of Carpenter’s best films.

THE THING

“I dunno what the hell’s in there, but it’s weird and pissed off, whatever it is.”

In The Thing (1982), a group of scientists in Antarctica encounter a shape-shifting alien that can imitate any living organism, leading to paranoia and terror as they struggle to determine who can be trusted amidst the growing chaos.

The Thing is John Carpenter’s masterpiece—a slow-burn, paranoia-soaked thriller that perfectly balances isolation, suspense, and escalating dread. While some viewers may find the film’s pacing deliberate on a first watch, it’s precisely that slow build that makes it so effective. It took me several viewings to fully appreciate its brilliance. At first, I was indifferent, but after inheriting a DVD copy from a roommate who skipped out on rent, it became part of my regular Halloween rotation. Over time, the film’s themes of mistrust and survival in a remote, claustrophobic setting really began to resonate. The way it depicts a small group slowly unraveling under the pressure of fear and suspicion is nothing short of masterful.

There’s something timeless about the formula—characters cut off from the world, forced to confront not just a deadly threat, but the possibility that anyone among them could be the enemy. It’s a scenario that feels just as gripping today as it did upon release. Flamethrowers help, of course, but it’s the suffocating atmosphere and the erosion of trust that truly define the film. For me, The Thing is the crown jewel of Carpenter’s filmography. While I revisit many of his works each year, this is the one I always return to without question. Like Big Trouble in Little China, it was ahead of its time, but unlike most genre films, The Thing has only grown more potent with age, standing alone as a perfectly constructed sci-fi horror classic.

BIG TROUBLE IN LITTLE CHINA

“Tall guy, weird clothes. First you see him, then you don’t.”

In Big Trouble in Little China (1986), a truck driver named Jack Burton teams up with a local friend to rescue a beautiful green-eyed woman from an ancient sorcerer in a magical battle beneath San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Big Trouble in Little China thrives on its own absurdity, fully embracing its identity as a genre-bending, high-energy B-movie. At the heart of it is Jack Burton—brash, clueless, and full of swagger—a less competent John Wayne who’s often out of his depth and rarely the one saving the day. As John Carpenter himself described it, the film is “an action adventure comedy kung fu ghost story monster movie,” and it somehow manages to be all of those things at once. The real twist is in how it flips the traditional 1980s hero dynamic on its head: Jack may get top billing, but it’s Wang who’s the real hero—skilled, brave, and driven—while Jack stumbles through the chaos, more comic relief than savior.

The film’s box office failure was likely the result of a perfect storm: a studio that didn’t know how to market such a wildly unconventional project, audiences unprepared for its postmodern tone, and a cinematic landscape not yet ready for the kind of meta-humor Carpenter was exploring—a tone that wouldn’t catch on until films like Scream nearly a decade later. But time has been kind to Big Trouble in Little China. It plays like a perfect Friday night flick or a Saturday matinee, blending martial arts mysticism, monster movie madness, and Carpenter’s signature deadpan humor. It’s self-aware without being smug, and unashamedly fun without being shallow—a cult classic that knew exactly what it was before the rest of us caught up.

THEY LIVE

“They are dismantling the sleeping middle class. More and more people are becoming poor. We are their cattle. We are being bred for slavery.”

In They Live (1988), a drifter discovers that the world is controlled by alien overlords who manipulate humanity through subliminal messaging, leading him to fight back against their insidious influence.

They Live is a fun, fast-paced sci-fi flick that wastes no time letting you know something weird is going on. The big reveal with the sunglasses is still one of Carpenter’s coolest moments, kicking off a story that blends B-movie charm with sharp (and very loud) social commentary. What really makes They Live stand out is how bold and on-the-nose it is—there’s nothing subtle about its take on capitalism, conformity, and political power. It feels even more relevant today than it probably did back in 1988. It’s clever, a little rebellious, and never takes itself too seriously, which is exactly what makes it so memorable.

THE 6TH PICK (Honorable Mention)

ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13

“There are no heroes anymore, Bishop. Just men who follow orders.”

In Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), a group of police officers and civilians must band together to survive a relentless assault from a ruthless gang of killers who have surrounded their precinct in a long, dark night of violence.

Like much of John Carpenter’s early work, Assault on Precinct 13 wasn’t a hit upon release and struggled at the box office, but eventually found its audience through home video and became a cult classic. Interestingly, the film was better received in Britain than in the U.S., where audiences recognized and appreciated its homage to American Westerns—a genre so familiar to American viewers that the film’s clever nods may have been overlooked. While the early pacing drags a bit and the dialogue can be cheesy, the characters carry it with charm, and the film’s visuals are a standout. Carpenter and his team put most of their budget into camera work and film processing, which pays off in the movie’s striking look—capturing the isolation of the police station and the eerie emptiness of the urban sprawl. It may not be his best film, but it’s pure Carpenter: stylish, moody, and a clear sign of the filmmaker he was becoming.

TRADEMARK | Albertus Typeface

TRADEMARK | Minimalistic Scores

I’m only posting three examples of his films scores below, but if you want to take a deeper dive into learning more about Carpenter and his scores, I would highly recommend the 14 minute video entitled, “The Musical Legacy of John Carpenter” on YouTube. It’s well worth your time.

THE FOG (1980)

Of all of John Carpenter’s early scores from the 1970s through the mid-1980s, The Fog stands out as his most atmospheric, perfectly capturing the eerie tone of a ghost story. It’s a moody, haunting composition that showcases Carpenter’s ability to craft a rich, suspenseful soundscape—subtle and expansive enough to build tension while still delivering an unforgettable melody.

ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK (1981)

Carpenter’s score for Escape from New York is probably my favorite of his, and it does an exceptional job of establishing the film’s tone. While there are subtle hints of heroism woven into the music, they’re deliberately restrained—never fully rising to the surface. Instead, the score leans into a sense of detached coolness, perfectly mirroring the film’s gritty, dystopian atmosphere and its anti-hero lead.

IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS (1994)

While most of Carpenter’s score for In the Mouth of Madness is steeped in atmospheric tension, it was the theme that plays over the opening credit sequence that really grabbed me. By the late ’90s, I had built up a pretty extensive CD collection of film soundtracks and original scores, and this was probably the second Carpenter score I deliberately hunted down (the first, of course, was Halloween). For reasons I still can’t quite explain, that opening track was on constant repeat—it was catchy, addictive, and oddly fitting, much like Sutter Cane’s books themselves.

TRADEMARK | Bleak Stories

Prince of Darkness is one of John Carpenter’s bleakest films, steeped in an atmosphere of dread and cosmic horror. It offers little hope, presenting evil not as something personal or emotional, but as an ancient, indifferent force beyond human understanding. The film’s conclusion reinforces this despair, leaving audiences with a haunting sense that the battle between good and evil may already be lost.

What makes the scene below so unnerving is Carpenter’s blending of science and theology, suggesting that evil isn’t just a spiritual or symbolic concept but a literal, ancient force governed by quantum mechanics and dark matter.

In the Mouth of Madness is steeped in Lovecraftian horror where the boundaries between fiction and reality dissolve into overwhelming chaos. It explores the fragility of sanity and the terrifying idea that collective belief can reshape the world, erasing objective truth. True to its cosmic horror roots, the film offers no resolution—only the chilling realization that madness has already won.

The scene below is a surreal gut-punch, reinforcing the film’s core theme: the collapse of reality under the weight of collective belief and fiction. Trent is no longer in control of his world (if he ever was in the first place).

TRADEMARK | Reluctant Heroes

Laurie Strode embodies the reluctant hero in Halloween, initially portrayed as a quiet, bookish teenager simply trying to survive the night. Thrust into a nightmare she never asked for, her strength emerges not from desire, but from necessity—a response to pure, unrelenting evil.

In They Live, Nada is a classic reluctant hero—an everyman drifter who stumbles into a hidden truth and is forced to act. He doesn’t seek out revolution, but once he sees the world for what it really is, he can’t ignore it, even if it costs him everything.

MacReady in The Thing is a reluctant hero defined by circumstance rather than choice, stepping into leadership only when paranoia and survival demand it. He doesn’t seek control or glory—just the grim responsibility of doing what needs to be done in a situation where trust is a luxury no one can afford.

KEY SCENES

Some of the scenes I’m about to highlight aren’t for the faint of heart. While some viewers might not be fazed by disturbing imagery, it’s worth noting that Carpenter is a master of horror—so consider this your warning: viewer discretion is advised.

The Blood Test

The blood test scene in The Thing is one of the film’s most nerve-wracking moments, built on layers of paranoia and mounting distrust. Tensions are already at a breaking point as the isolated group realizes that anyone among them could be the enemy in disguise. With no one left to trust, the blood test becomes a desperate attempt to uncover the truth—and the suspense is nearly unbearable as each person waits to see what will happen when their blood is put to the test.

“Show Me”

In this scene from Christine, Arnie is heartbroken after discovering that his beloved 1958 Plymouth Fury has been viciously vandalized by bullies. Standing in the garage, overwhelmed by loss and frustration, he speaks directly to the car, pleading for it to come back—and miraculously, it responds. As the car begins to repair itself, piece by piece, in a stunning display of supernatural power, Carpenter and his crew showcase their mastery of practical effects, using reverse photography and ingenious mechanical rigs to create one of the most memorable and eerie moments in the film.

Nada Puts on the Sunglasses

In They Live, the moment Nada first puts on the special sunglasses marks a dramatic shift in the film’s tone and direction. What seems like an ordinary city street is suddenly revealed as a hidden world of subliminal messages and inhuman figures disguised as people. The scene is both shocking and surreal, capturing Nada’s confusion and horror as he realizes the truth—and setting the stage for the rebellion that follows.

Michael’s First Kill

The opening scene in Halloween is a masterclass in suspense and visual storytelling. Shot in a continuous, unbroken point-of-view take, the camera assumes the perspective of an unknown stalker silently creeping through a suburban home on Halloween night. The tension builds as the figure grabs a knife, dons a clown mask, and brutally murders a teenage girl—only for the shocking reveal to come moments later: the killer is a young boy, Michael Myers.

“It’s All in the Reflexes”

Kurt Russell’s Jack Burton flips the action hero trope on its head in Big Trouble in Little China. Instead of the competent lead and goofy sidekick dynamic, Jack is the bumbling comic relief while his “sidekick” does most of the heavy lifting. But in the final showdown with Lo Pan, Jack surprises everyone by catching a thrown knife and killing the villain, proving Carpenter’s sharp instincts not just in horror, but in action filmmaking as well.

Further Viewing – A Cultivated Selection

UNDERRATED OR OVERLOOKED GEM

I wasn’t sure how I felt about The Fog the first time I saw it. It never seemed like a high-priority Carpenter film, and some video rental stores didn’t even carry it. But with repeat viewings and a more seasoned appreciation for slower, mood-driven horror, the film really started to shine. It’s not a slasher or gore-fest—so those looking for that may be let down—but its strength lies in its eerie atmosphere and deliberate pacing. The Fog is a low-budget ghost story that builds tension through tone, making it an often overlooked gem in Carpenter’s filmography.

PERFECTLY PAIRED WITH POPCORN

I was definitely late to the party when it came to Christine (1983). I knew it was based on a Stephen King novel, but for the longest time, I had no idea it was directed by John Carpenter (yes, even I miss the obvious sometimes). Then about ten years ago, I stumbled across it while streaming and decided to give it a shot—and I’m so glad I did. There’s a real joy in unearthing an underrated ’80s gem like this one, especially when it’s handled with such precision. Carpenter’s direction is lean and focused, delivering a taut, mean horror film that wastes no time getting under your skin. The cinematography and camera work are quietly brilliant, capturing both the eerie menace of the possessed car and the tragic unraveling of its owner with style and restraint. Christine may not always get mentioned alongside Carpenter’s more iconic films, but it absolutely deserves a spot in the conversation.

GUILTY PLEASURE

Back in the early days of the internet, I was obsessed with finding and downloading movie trailers. I’d spend countless late nights tethered to my dial-up modem, patiently waiting for a massive QuickTime .mov file to finish downloading on my old Windows PC. I must’ve downloaded dozens of trailers during the late ’90s, but the first three that still stand out in my memory are Mission: Impossible, Lone Star, and Vampires—the last of which is the one I’m sharing with you below.

Now that was a bit of a lead-up just to show you a trailer that may or may not not have impressed you in any way, but 22-year-old me was, very much so. At the time of its release, it felt like a very original take on the vampire myth. John Carpenter’s Vampires is a gritty blend of Western swagger and gory horror, swapping out cloaked, romanticized vampires for brutal, feral predators. The film leans into practical effects that are skillfully executed and often disgustingly realistic, adding to its visceral punch. While it lacks some of the thematic depth found in Carpenter’s stronger work, it’s still a fun, rough-around-the-edges ride—a guilty pleasure with cowboy boots and blood.

Until Next Time, Dear Readers.

Leave a comment